Power Imbalance

Narratives of charismatic men and women are commonly portrayed within the media which use coercive control and manipulation to get what they want. This portrays an extreme and often unrealistic picture of narcissism and controlling behaviours leading to a power imbalance.

However, power imbalances in real relationships are often less extreme but are more common than you think. In fact, one in six women and one in sixteen men will experience sexual or physical violence in their life and one in four women and one in four men will experience emotional abuse by a current or previous partner in Australia (AIHW, 2018).

Narcissistic Personality Disorder is found in 6.2% of the population (Dhawan et al., 2010). Traits of narcissism, such as a grandiose sense of self, need for admiration and lack of empathy are observable without a personality disorder. Although they may not show it outwardly, people with narcissistic tendencies have a vulnerability to their self-esteem and find it hard to cope with criticism or loss.

Unfortunately, this leads to a complete disregard for other people’s feelings and a sense of entitlement within interpersonal relationships. It’s important to note that not everyone who uses power to control another person is necessarily narcissistic and not all people with narcissism are controlling.

The Power Imbalance

Power imbalance begins to occur when things like respect, independence, and integrity are removed and replaced with control by means of intimidation, abuse and lack of empathy. Power imbalance can occur to anyone and by anyone.

But someone has to wear the pants, right?

Not really. Of course, individual couples tend to willingly adapt to the cultural expectations about gender roles. Within an imbalance of power, the powershift is unwanted.

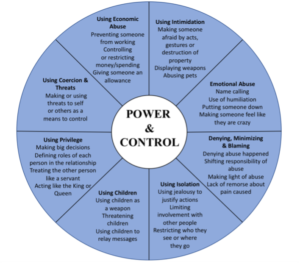

(Adapted from the Duluth Model, Pence & Paymar, 1993)

Irregular behaviours are significantly different from ones that are frequent and used to create control of someone in the long term. When someone engages in behaviours to exert control over another person, it usually means that internally, they feel a lack of control, and are trying to protect against strong negative emotions.

For example, when a person is visibly aggressive in a confrontation, this may be to protect themselves from difficult feelings such as shame and guilt whilst maintaining dominance and power. Whereas minimising and denying, shifts any responsibility from an individual’s actions and places blame onto the other person whilst removing their right to warmth and empathy. Therefore, a power shift occurs to control another person into submission.

Where Can This Occur?

Sometimes a power imbalance is expected:

- At work: Employees have an expectation to work within their abilities and role

- In a healthy child-adult relationship: Adults are responsible for a child’s safety.

However, a power imbalance where control tactics are causing distress to an individual is not acceptable. These can occur beyond romantic relationships including friendships, family dynamics, and occupational settings.

How To Balance The Imbalance

While every relationship will have a balance of power based on the type of relationship it is, no one should be in complete control and power.

Step 1

- Assess the relationship

- Does there appear to be an imbalance of power by either or both people according to the Power and Control Wheel?

Step 2

- Reflect on boundaries and respect in the relationship

- If there appears to be a lack of respect and boundaries think about what you would like from these things

Step 3

- What is the function of imposing power tactics to gain control? How is conflict handled?

- Often people use power tactics to confront everything but the issue. It might be important to ask, “am I avoiding the issue altogether?”

Step 4

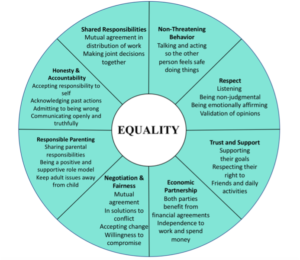

(Adapted from the Duluth Model, Pence et al, 1993)

- Stick to the topic at hand

- Try and gauge the problem from both people’s perspectives. Prioritise respect for autonomy and understanding of the other person’s feelings and affirm their emotions.

- Have conversations about expectations and what is unacceptable.

Step 5

- Find the common goal

- When there is a problem, there is usually a common goal. When two people are on the same side, you will be able to tackle any issue as equal teammates who support one another.

Positives ways of interacting with a person prioritise respect, accountability, autonomy, compassion and fairness. There will always be interpersonal conflict and disagreements within a relationship, however, a healthy one does not use power as a method to control the other.

References

Australian Institute Of Health and Welfare (2018). Family Domestic and Sexual Violence in Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/family-domestic-sexual-violence-in-australia-2018/summary.

Dhawan, N., Kunik, M. E., Oldham, J., & Coverdale, J. (2010). Prevalence and treatment of narcissistic personality disorder in the community: a systematic review. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51(4), 333-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.09.003

Pence, E., Paymar, M., & Ritmeester, T. (1993). Education groups for men who batter: The Duluth model. Springer Publishing Company.